Important & superlative early Royal Flying Corps ‘Deeds That Thrill The Empire’ DSO group , OBE. & 1914 Star & Bar trio , Lieut. Somerset L.I. attd R.F.C. /Lieut Col. R.F.C. awarded for dropping a bomb squarely on a troop train in Don Station , March 1915. A founding officer of the Royal Flying Corps – who qualified as a pilot at Brooklands in 1912 . Flew a lengthy and daring reconnaissance in the Battle of Le Cateau 26 August 1914 having earlier. been credited with the first successful bombing being a transport vehicle park: downed by ground fire, he took to a bicycle and a car, and delivered an important intelligence report on reaching his base at midnight. Also credited with flying the first ever photographic reconnaissance sortie – when he took five photographs of enemy positions on the Aisne on 15 September 1914 – and for experimenting in night flying etc. etc.

£7,450.00

Out of stock

Distinguished Service Order, (GV)., silver-gilt and enamel, O.B.E. 1st type Military, 1914 Star, & clasp (Lieut. Som. L.I. Attd. R.F.C.), British War Medal, Victory Medals, with M.I.D. oak leaves (Lt. Col. R.F.C.),

George Frederick Pretyman

D.S.O. London Gazette 27 March 1915:

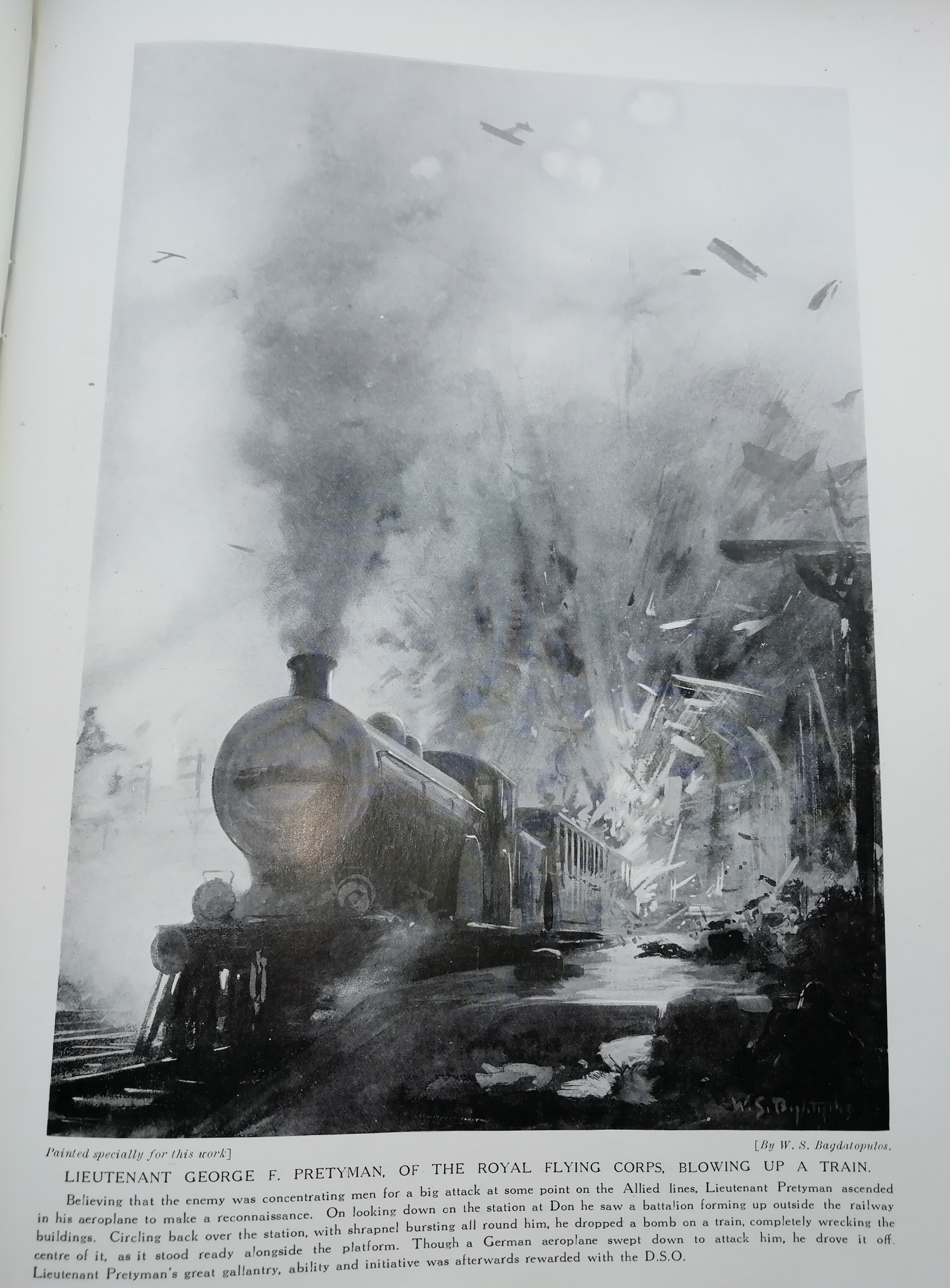

‘For great gallantry, ability and initiative on numerous occasions, especially on the 12th inst. The clouds being low, he had to fly very low for a considerable period all along the German positions to ascertain their movements, being exposed the whole time to a very heavy fire. On the 13th inst. he blew up the centre of a train at Don station, damaged a building outside which a battalion of the enemy were forming up and drove off a German aeroplane.’

O.B.E. London Gazette 1 January 1919: ‘In recognition of valuable services rendered in connection with the war.’

Mentioned in Despatches, London Gazettes 27/3/1915, 15/6/1915, 22/6/1915, and 11/12/1917

George Frederick Pretyman was born on 8 September 1891, eldest son of Major-General Sir George Pretyman, K.C.M.G., C.B. Educated at Wellington College , he was commissioned in the Somerset Light Infantry in March 1911, Lieutenant in April 1914. He qualified for his Pilot’s Certificate (No. 341) on a Bristol biplane at Brooklands in October 1912. Having then attended the Central Flying School, he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in September 1913.

Pretyman flew to France in a Bleriot Parasol on 13 August 1914, as a member of No. 3 Squadron. On the 26th, having taken off from Honnechy at 11.50 a.m,, he flew an armed reconnaissance flight with Major L. B. Boyd-Moss as his observer. It was a lengthy flight of three hours duration, to Le Cateau, Valenciennes and Cambrai and during which they gathered valuable information about enemy troop movements. Along the way, they dropped their single bomb on a park full of transport vehicles near Blaugies, observed Cambrai in flames and in German hands, and were engaged by howitzers whilst over Le Cateau.

At 1.40 p.m., west of Cambrai, German infantrymen opened a rapid and accurate fire on them, one round putting their engine out of action. Pretyman skilfully glided the stricken Bleriot two miles to the west, to avoid the enemy, and on landing destroyed the aircraft. He and Boyd-Moss then joined up with a retreating French cavalry heading towards Arras, prior to travelling by bicycle and by car back to their base. Arriving around midnight they were able to deliver their recce report for onward dispatch to Army Headquarters.

On his next flight Bleriot enjoyed similar luck, when owing to engine trouble he had to wreck and burn the aircraft at Bouex. In Flying Fury, James McCudden – the future V.C. then serving with 3 Squadron – recalled that on this occasion Pretyman and his observer were missing for several days, as they made their way south on foot. But he rejoined the squadron in time to extend his pioneering work to flying the first ever photographic reconnaissance – over the Aisne – on 15 September 1914.

He returned to base with five photographs of enemy positions, which became the forerunners of an immense – regularly updated – photographic map of the Western Front, which played such a significant part in planning and operations. In an artillery observation flight to Hinges in early December 1914, Pretyman’s aircraft took a ‘bullet through the petrol tank’, whilst in a recce on the 21st he reported of ‘heavy rifle fire’ being experienced along the Givenchy-Neuve Chapelle sector. And it was in the vicinity of the latter location.

As Temporary Captain and Flight Commander he won his D.S.O. in March 1915, for daring reconnaissance work and his spectacular attack on the railway station at Don on the 13th, the latter deed being featured in Deeds That Thrill the Empire:

‘On looking down on the station of Don he saw a battalion forming up outside the railway buildings. Circling back over the station, with shrapnel bursting all round him, he dropped a bomb on a train, completely wrecking the centre, as it stood ready alongside the platform. Though a German aeroplane swept down to attack him, he drove it off. Lieutenant Pretyman’s great gallantry, ability and initiative were afterwards rewarded with the D.S.O.’

On the previous day he had undertaken two flights to locate the ongoing line of battle. As recalled by McCudden V.C. in Flying Fury, Pretyman reported that the enemy still held positions between Neuve Chapelle and the Bois de Biez, but that, despite the strength of the German attacks, the British troops were maintaining their hold on the eastern edge of Neuve Chapelle village. It was yet another pioneering sortie, the type of work that McCudden would describe as ‘brilliant’. Rather like Pretyman’s pioneering night flying, to which he also refers. McCudden also to referred to Pretyman’s courage in trying to rescue injured personnel after two Melonite bombs exploded during the loading process. He was among ‘the little band of helpers who assisted at the risk of their lives.’

On 5 May 1915, with Captain J. H. S. Tyssen as his observer he helped force down an enemy two-seater near Lille. The relevant combat report states that they were on a reconnaissance in their Morane L, flying at 5,000 feet, when they met a ‘Fokker (or Morane) Parasol … clearly marked with black crosses’ and ‘more silvery in colour than our Moranes’: ‘Hostile machine sighted over Don, was chased and gradually overhauled. Opened fire at 100x. After about 20 or 30 rounds the Fokker dived vertically underneath our machine. Captain Tyssen last saw it still going down over a ploughed field near Lille. Further observation was impossible owing to anti-aircraft fire.’

Ten days later, flying without an observer on a bombing mission to the Bois de Biez-Fournes sector – and armed only with a Webley automatic pistol – he engaged a German L.V.G. bearing ‘dull red crosses’: ‘ … I had just chased another machine towards Fournes but had not got close and went off to get more height in case another of the same should come back again. Went up to 10,000 feet and then saw a machine coming towards our lines at about 7,000 feet. It turned when over Aubers, having apparently got close enough to our lines. I then dived down to within 20 feet on top of him and on getting level just above him opened fire with 1 charged W. Scott Automatic Pistol. He immediately did a banked turn away, diving at the same time. When I had reloaded he was too far down to chase. He opened fire when I was reloading and disappeared very low down towards Lille.’

His immediate award of the D.S.O. for his earlier exploits aside, Pretyman was also twice mentioned in despatches. He was ‘rested’ with an appointment at the Central Flying School in July-November 1915.

As Temporary Major, he returned to France as C.O. of No. 1 Squadron in November 1915, and remained until October 1916. Soon after his arrival, on taking a Morane to St. Omer to collect a new aircraft, his observer, 2nd Lieutenant D. C. Cleaver, in a freak accident, fell out of the aircraft at 1,200 feet. Cleaver was 17-years-old and a distraught Pretyman was offered leave by Trenchard, but he declined the offer. Pretyman continued to see further action – a combat with an Albatros at 11,000 feet over Hollebeke on 24 February 1916 but owing to serious loss of life amongst experienced C.O.s, Trenchard eventually forbade them to fly within five miles of enemy lines.

As Lieutenant-Colonel – and he commanded No. 13 Wing in France during part of 1917, gaining his third ‘mention’ (London Gazette 11 December 1917, Pretyman ended the war as a senior staff officer in the Department of the Deputy Director of Training at the Air Ministry and was granted the rank of Wing Commander in the Royal Air Force, and awarded the O.B.E. He was placed on the Retired List in November 1929 and died at Alresford, Essex in June 1937, aged just 45