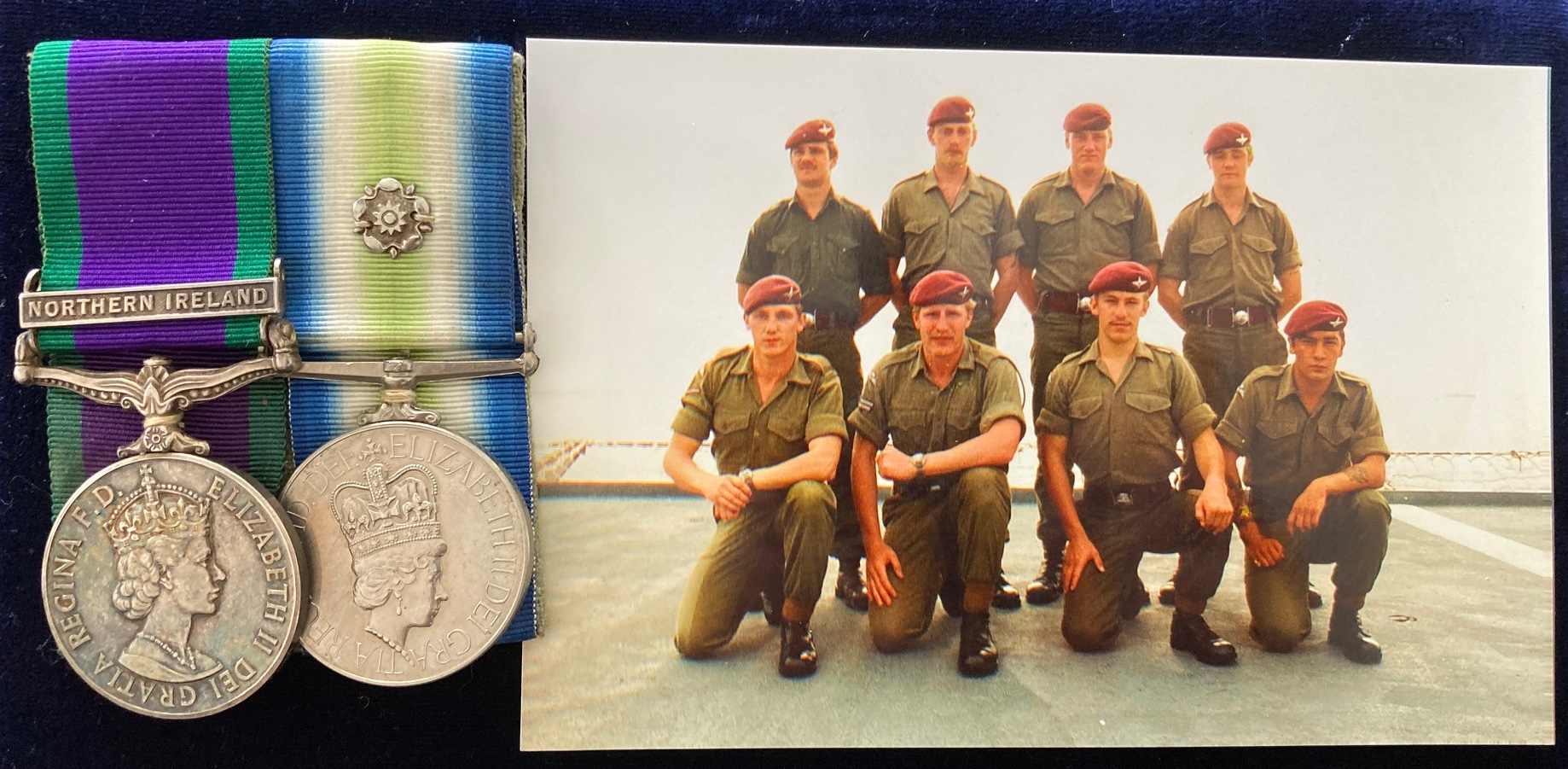

C.S.M. clasp Northern Ireland, South Atlantic with Rosette, Pte. , Para . Served 10 Platoon, D Company 2 Para (Major Phil Neame’s Company at Goose Green who’s friction with ‘H’ is well documented)

£2,900.00

Out of stock

C.S.M. clasp Northern Ireland, South Atlantic with Rosette,

Pte. T.A. Connor, Para

Court mounted as worn

Served 10 Platoon, D Company 2 Para (Major Phil Neame’s Company at Goose Green who’s friction with ‘H’ is well documented)

With copy Certificate of Service which specifically mentions the recipient’s ‘Excellent and courageous service in the Falklands.’

Mentioned in text regarding the assault of the main Argentine defensive position at the Boca House

‘We then proceeded to try and neutralise the Boca House position with well controlled fire control orders. Privates Lewis and Connor reckon they managed to hit an Argentinian who got out of a bunker.’

The Battle for Darwin and Goose Green, Friday 28th May – At 3.30 am, A Coy moved off on the left and attacked Burntside House believed to be occupied by an Argentine platoon, but found no-one there other than four unhurt civilians. At 4.10 am, B Coy started forward from the other side of Burntside Pond down the right flank with D Coy following them long the middle. With artillery support on both sides, B and D Coy’s were soon in confused action against a series of enemy trenches, and as they slowly made progress, A Coy moved past unoccupied positions at Coronation Point. Leaving one platoon of A Coy to provide covering fire from the north side of Darwin, the remainder started to circle round the inlet to take the settlement. As dawn broke, the attacks on both flanks bogged down as B Coy came up against the strongpoint of Boca House and A Coy found that a small rise, later known as Darwin Hill, was the key to the Argentine defences.

‘Not until midday did 2 Para break through. As A Coy was hit and went to ground, Lt Col Jones and his Tac HQ came up, and another attempt to push forward was made which led to two officers and an NCO being killed. Col Jones moved off virtually on his own, and was soon shot and dying in an action which led to the award of a Victoria Cross. Maj Keeble was called up from the rear, and leaving A Coy to slowly wrest Darwin Hill and pulling B Coy slightly back from Boca House, ordered D Coy to move round them on the far right along the edge of the sea. Now in daylight, the battle continued with the Argentines helicoptering in their first reinforcements and flying more support missions. The first attack by Falkland’s based aircraft took place earlier when a Grupo 3 Pucara was hit, probably by a Blowpipe SAM, but limped back to Stanley. The next sortie by two more Pucaras caught two Royal Marine Scouts on their way in to casevac Lt Col Jones. Capt Niblett managed to evade them, but Lt Nunn was killed by cannon fire and went down near Camilla Creek House [b28]. One of the Pucaras was later found to have crashed into high ground returning to Stanley [a58].

By midday, A Coy had taken and held Darwin Hill, and B and D Coy’s had finally silenced Boca House. Still under fire, D and C Coy’s headed towards the airfield and Goose Green while B Coy circled east to cut off the settlement. During the attack towards the schoolhouse, three men of D Coy were killed in an incident involving a white flag. Now into the late afternoon, aircraft from both sides came on the scene, starting with two MB.339’s of CANA 1 Esc and two Pucaras of Grupo 3 which hit the school area. One of the Navy jets was brought down by a Royal Marine Blowpipe [a59], and minutes later one of the Pucaras dropped napalm and the other shot down by small arms fire [a60]. Then three Harrier GR.3’s brought much needed relief by hitting the AA guns at Goose Green with CBU’s and rockets.

With evening approaching and the Argentines squeezed in towards Goose Green, more reinforcements arrived to the south by helicopter, while to the north, J Coy 42 Cdo was flown in reinforce 2 Para but too late to join in the fighting. Two Argentine POW’s were sent in to start negotiations which lasted most of the night, and next morning, Group Capt Pedroza surrendered all his forces to Maj Keeble. British losses were fifteen men from 2 Para, a Royal Engineer and the Marine pilot, and 30 to 40 Paras wounded. Many of the 1,000 Argentine POW’s including the FAA men sailed on “Norland” to Montevideo in early June.’

Later written by member of ‘D’ Company (Geddes)

‘On the ground, H was furious to discover that D Company, which should have remained in reserve, had some-how managed to get lost and ended up in front of him. “What the hell are you people doing here?” he asked their boss Major Phil Neame after bumping into the back of them as he marched along.”You lot shouldn’t be in front of me. My orders were quite f****** clear.” The lads in D Company didn’t have a lot of time for H, probably out of loyalty to Phil Neame, who they lionised.He was pure para, unlike H who they regarded as a blow-in, and they felt H saw him as competition. Certainly, it seemed to me that the colonel was barely civil to Neame most of the time and the friction between them would become more apparent as the battle continued. H strode forward with his command team but before long they came under enemy fire. Reluctantly, they made their way back to D Company’s position where he told Neame to clear the enemy off the track ahead. The problem was that no one knew where the enemy were. Not Neame or the colonel or anyone else.The battle was beginning to defy the maps and strategies and take on a life of its own. Fate would take lives or spare them and decide who would get the victor’s spoils. And there was little H could do about it. As D Company followed his orders and moved forward, Argy guns erupted in the night, opening up on them from only 40 yards away. Undaunted, they started crawling straight towards the enemy trenches, rounds constantly whining over their heads. Within the space of 20 minutes, three good men were killed.

Meanwhile, H was trumpeting down the radio, nagging Major Neame. “Get a move on!” That was the clear message from the boss, whose tendency to micro-manage had burst to the fore and got worse as the battle went on. Soon it extended to A Company, who had encountered hardly any enemy resistance. They were eager to press onwards to Darwin Ridge – a row of hills that contained the main Argy line of defence. If they were to avoid being spotted, it was vital they proceed under cover of darkness but H sent an order to wait for him to arrive so he could assess the situation himself….

But the lull in the battle did not last long. His timetable torn to shreds, H arrived in the Gorse Gully at 8.20am. Striding out in front of his team, he was in no mood to accept suggestions from anyone as to how he should move things on, least of all Phil Neame of D Company. By then, Major Neame and his men were within 300 yards of a narrow shingle beach and he radioed the colonel to suggest they sneaked along it to get past the enemy positions and then come round on the Argies from the back.

The agitated H was having none of it – as we heard over the airwaves. “Don’t try to tell me how to run my f****** battle,” he snarled at Neame in his clipped public-school accent. Why had H done it? Why had he charged up that gully? It seemed like madness to us. We cannot shirk from the fact that H unravelled at Goose Green. I’m a soldier and I don’t criticise him for it in any angry sense because I understand the pressure he was put under by the task force command, who left him without air and sea support, proper intelligence or even basic supplies of ammo. But H also put pressure on himself. His refusal to give his officers their head and trust their judgment that day was a real problem.

D Company could have made their move along the beach early in the battle but H just gave Phil Neame an ear-bashing over the suggestion.

Even harder to accept was his rejection of Captain Ketley’s offer to hit the Argies on the ridge with rockets. We know that H was conserving the rockets to deal with armoured vehicles later in the conflict, but they were far less of an immediate threat than the bunkers blasting hell out of us in the gorse gully. Should he have got the VC? Well, certainly the battalion deserved a VC and in that sense the award to its colonel may have some justice in it. I believe H’s dash into action was motivated by anger, passion and regret at the loss of his friend Dave Wood. When he realised Wood was dead, he decided to do what he believed was the honourable thing and try to sort it out himself. His judgment was unbalanced and what he did was lionhearted but illconceived and futile. It didn’t make a difference to the battle.

The simple fact is that H should never have insisted on being so close to the action. We needed him near but not underfoot and he should have been conducting the battle, not fighting it. He was the colonel; we were the cannon fodder. His “get your skirts off” call to arms was not inspiring and his action was all risk and no calculation. What’s more, contrary to the citation for his Victoria Cross, he never fired a shot. Nothing that I say is a criticism of H, even if it does sound harsh. Toms don’t think that way.’